| 1-528KP-40 | |

| Location | Russia Russia: St. Petersburg, Leningrad region, Veliky Novgorod, Petrozavodsk, etc. |

| Construction | 1962 - 1970s |

| Usage | House |

| Height | |

| Roof | about 35 meters |

| Top floor | about 30 meters |

| Technical specifications | |

| Number of floors | 9 |

| Number of elevators | 1 |

| Architect | "Lenproekt": N. N. Nadezhin and V. M. Fromzel |

1-528KP-40

(unofficial name

“Nadezhina point”

) is a standard series of brick residential buildings “points” built from 1962 to the 1970s in Leningrad, as well as some other cities. The authors of the project are famous Soviet architects N. N. Nadezhin and V. M. Fromzel. Initially, the individual project was highly appreciated in the professional environment and was soon approved as a standard one. The house was noted for publications in prestigious foreign publications L'Architecture d'aujourd'hui (French)Russian. (France) and The Architectural Review (English) Russian. (UK) in 1964 and 1965.

History of creation

In 1961, at the Lenproekt Institute in workshop No. 3 of O.I. Guryev by architect N.N. Nadezhin under the leadership of the master of Stalinist neoclassicism V.M. Fromzel developed a project for a nine-story brick “spot” residential building with 45 apartments[1][2].

This is how the idea for this house was born. I was sitting at some meeting at the Union of Architects, turning in my hands an empty box of Kazbek cigarettes, on which a horseman rides, if you remember. He opened the box and began to draw.

- V. M. Fromzel, St. Petersburg Gazette No. 22 (2412), February 3, 2001

[3]

It is noteworthy that the individual project was initially created by order of one of the first housing and construction cooperatives in the USSR, Mayak, in the Vyborg district of Leningrad. During the design, the decisions of the meeting of future residents were taken into account. The first buildings were built in 1962 at the addresses Dresdenskaya Street, building 26[4], and Thorez Avenue, building 90[1][5].

The project became an event in the architectural and construction practice of Leningrad. In contrast to the typical faceless large-panel “Khrushchev” buildings that were widespread at that time, the new buildings had a simple, but unique plastic appearance: alternating multi-colored bricks in the facades, “interrupting” the number of floors, a memorable ratio of blank walls, loggias, openings[1][2 ].

The apartments in these houses had an improved layout for that time: more spacious kitchens and rooms, no rooms of “carriage” proportions, rooms with windows on two sides, spacious “two-room apartments” instead of cramped “three-room apartments.” The small construction area of the building (about 300 m2) made it easy to “introduce” it into a variety of areas and neighborhoods, in contrast to extended panel buildings that were much less maneuverable from the point of view of urban planning. In addition, these nine-story buildings were relatively inexpensive to produce. In fact, this project became one of the first signs in overcoming the “Khrushchevism” in mass construction, both in terms of external “decoration” and standards of planning and footage [1][2][6][7][8][9].

These features made the project very popular not only among professional architects, but also ordinary citizens. It was recommended for reuse, and was soon approved as a standard model under the number 1-528KP-40

. The project became an all-Union project and was often used in cooperative construction. In total, more than three hundred houses were built on it in Leningrad[1][2]. As critics have noted: “A house that has been sold many times remains an example of achieving an expressive result using the most meager means”[10]. According to Professor Yu.I. Kurbatov, the Nadezhinsky project “saved” the development of new quarters of Leningrad from “gloomy monotony”[11].

The typical tower house received its unofficial name in honor of the author - “Nadyozhina point”, becoming the only such example in Leningrad. The project was noted for publications in prestigious foreign publications L'Architecture d'aujourd'hui (French)Russian. (France) and The Architectural Review (English) Russian. (Great Britain) in 1964 and 1965, and the architect N.N. Nadezhin gained all-Union fame[1][2][7].

Project Features

The first designs of houses from the time of Khrushchev contained references to tiled or slate roofs, but were already distinguished by a characteristic layout. However, at that time there was a widespread campaign against architectural excesses.

The unspoken instructions that party workers followed contained a statement to reduce the cost of building such a house as much as possible. Therefore, all subsequent projects of such five-story buildings already featured significantly cheaper flat bitumen roofs.

For the same reason, any stucco elements or other decorative finishing options characteristic of Stalinist high-rise buildings were rejected by the Khrushchev projects.

Khrushchev refrigerator

When you enter the kitchen in an apartment in a brick Khrushchev house, you can see a built-in closet under the window. It is intended for storing food.

Due to the fact that the thickness of the outer wall in such a cabinet is only half a brick, and sometimes this wall contains an eternally open hole, in winter such a cabinet can be used as a refrigerator.

The apartments themselves in Khrushchev-era buildings in winter are characterized by rather low temperatures due to poor thermal insulation of the walls. Therefore, such houses are also popularly called “Khrushchev refrigerators.”

Description

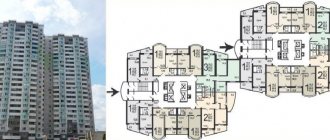

The series consists of nine-story “spot” brick buildings with 45 apartments. The construction area is about 300 m2. The external walls are made of unplastered brick, in most cases silicate (gray) with red ceramic inserts. The ceiling height is 2.5-2.7 m. The ceilings are made of hollow-core flooring with a screed having a felt base [7][8][9].

The apartments are 1,2,3-room, there are 5 apartments on each floor (1-1-2-2-3 rooms, total area - 33, 34, 47, 50 and 57 m2, respectively), and two of them are located half a floor higher than the other three. The apartments are separated from each other by main walls; the walls inside the apartments are not load-bearing. The rooms are quite spacious, there are no “corridor” types. One-room apartments have a combined bathroom, while others have a separate one. Living rooms - 10-20 m2, Kitchen - from 6 to 8 m2. Almost all apartments have windows on two sides and have a balcony or loggia[7][8][9].

The houses are equipped with a passenger elevator and a garbage chute, which run in the center of the landing and do not border any of the apartments, thanks to which the house has good sound insulation. Three apartments open onto the main landing, which has a spacious loggia[7][8][9].

In Leningrad, buildings of this series were built en masse in the 1960s, most often along the red lines of 5-story Khrushchev blocks, less often forming their own ensembles, for example, around the Serebryany Pond in the Vyborg district [1] [2].

The series was built from 1962 to the 1970s[3][6].

Construction period

The main construction of such houses was carried out in the period from 1959 to 1985. In Leningrad, the last brick Khrushchev building was completed in the 1970s. Then they were replaced by houses, popularly called “ship houses”.

In general, about 290 million square meters were built in Russia. m of total area, which is approximately 10% of the total housing stock available in the country. Such widespread construction became a stronghold of urban trends, and also significantly improved the living conditions of many people.

Modifications

It is known that there are several serial modifications of houses of the 1-528KP-40 series.

The first, earlier, “classical” one, was built almost exclusively in Leningrad and its suburbs. Outside the city limits on the Neva, it is also found in Vyborg and Veliky Novgorod[13].

Subsequently, when adapting the project for Sosnovy Bor, the so-called “spot serial configuration for 45 apartments for suburbs and gated communities” was developed. This was required by new fire safety rules: an additional escape staircase was added to the structure of the house. Buildings of this modification are distinguished by additional balconies and a small protrusion on the rear facade, and sometimes by the external finishing material. This variant is found mainly in the Leningrad region and other regions of Russia, and in St. Petersburg it is, for example, in Krasnoye Selo[2][14].

There are also buildings with various more or less significant design features. For example, houses 74 and 104 k1 on Torez Avenue have a small one-story extension, house 39 on Svetlanovsky Avenue is closely attached to the neighboring house of series 1-528KP-41/42. The buildings at 113 Metallistov Avenue and 53 Kondratyevsky Avenue have been significantly changed: they have 4 apartments per floor, all on the same level, a total of 32, 1 floor is non-residential. The buildings on Kolpinskoye Highway 12 and 47 are complemented by large attached loggias. In Gatchina, on Academician Konstantinov Street 5 and 7k1, the houses have a large one-story extension with non-residential premises and a partially non-residential first floor. In the houses at Zheleznovodskaya 31, 33 and 35, in a three-room apartment, one window was moved from the front facade to the side.

Liquid housing

Often, many series of 5-story brick houses were built as entire microdistricts. Often such houses were built several at a time on the street.

Since then, the courtyards with such houses have been greatly transformed: tall trees and various bush plants have grown in them.

Interior

In Khrushchev's apartments of a small area, it is very interesting to implement even the most original design ideas, the main idea of which is to give as much functionality as possible to a limited area:

- some people remodel the kitchen, combining it with the next room;

- someone demolishes a closet, thereby making the bedroom a little larger;

- someone demolishes absolutely all the partitions inside the apartment with their own hands, turning it into a studio apartment;

- Also, sometimes two apartments are bought at once on two floors of one riser and a single two-level apartment is made.

Thus, according to many residents, Khrushchev apartments are comfortable housing.

Notes

- ↑ 12345678

Nadezhina, 2014, p. 39-41, 150. - ↑ 12345678

Lavrov, 2008. - ↑ 12

Pozdnyakov, 2001. - [gorod.gov.spb.ru/facilities/19814/info/ Committee on Informatization and Communications of the Government of St. Petersburg. Portal “Our St. Petersburg”. House at the address: St. Petersburg, Dresdenskaya street, building 26. Technical and economic passport of an apartment building]

- [gorod.gov.spb.ru/facilities/54654/info/ Committee on Informatization and Communications of the Government of St. Petersburg. Portal “Our St. Petersburg”. House at the address: St. Petersburg, Torez Avenue, building 90. Technical and economic passport of an apartment building]

- ↑ 12

Myars, 2010, p. 55. - ↑ 12345

Urban, 2014. - ↑ 1234

Urban, 2013. - ↑ 1234

Kharitonov, 2014. - Nadezhina, 2014, p. 41.

- Nadezhina, 2014, p. 150.

- Minsk: Kalinovskogo street, 23A, Logoisky tract, 30 building. 4. Veliky Novgorod: Alexander Nevsky embankment, 25, 27, 29. Vologda: Nekrasova street, 63, 65, 67, 69. Obninsk: Zvezdnaya street, 5, 7, 9, 11, Komarova street, 7, 11, Lenin Avenue , 92, 108, 120, 124, Engels street, 15, 17, 19. Kirovo-Chepetsk: Alexey Nekrasov street, 7, 17, 19, Vyatskaya embankment, 1, 3, 10, 11, Kirova avenue, 11, 13, 15, Lenina street, 12, 12A, 64 bldg. 4, 66 bldg. 4, Mira Avenue, 43D, 43E, Pervomaiskaya Street, 3, 5, 7, 9, Yakov Tereshchenko Street, 7, 9, 11, 17, 19, 21. Zheleznogorsk: Kurchatova Avenue, 18, 30, 38. Polar Dawns: Nivsky Prospect, 1, 3, 5, 15, 16. Kondopoga: Bumazhnikov Street, 14, building 1, 2, 3, 4. Petrozavodsk: Zagorodnaya Street, 26, Marshala Meretskov Street, 21, 28. Novouralsk: Komsomolsky Prospekt, 13 , 17, 21, Furmanova street, 33, Birch alley, 7. Smolensk: October Revolution street, 24, 26, 28. Komsomolsk-on-Amur: International Avenue, 2 bldg. 2, 6 bldg. 1 and 2, 8, 35, 37, 39. Khabarovsk: Gogol street, 5, 7. Ozersk: Semenova street, 11, 19, 21, 25. Dimitrovgrad: Lenin Avenue, 9, 11, 13, 17, 22, 24 , 26, 28, 40, 42, 44. Ulyanovsk: Ablukova street, 59/7, Northern Venets street, 14, 16. Snezhinsk: Lenin street, 37.

- Vyborg: Batareinaya street, 2, 4, 6, Krivonosova street, 17, Kuibysheva street, 17, Pervomaiskaya street, 13, Primorskoe highway, 4, 6, 8, 10 Repin street, 7. Veliky Novgorod: Alexander Nevsky embankment, 25, 27, 29.

- Krasnoe Selo: Gatchinskoye Highway, 7 bldg. 2, Kingiseppskoe highway, 10 bldg. 3, Krasnogorodskaya street, 19 building. 3, Lenin Avenue, 73, Lermontov Street, 9, Narvskaya Street, 10, Osvobozhdeniye Street, 22, 26, 30, 34

Literature

- Nadezhina I.G..

Architect N.N. Nadezhin. Projects, buildings, painting, drawing / box. I. P. Dubrovskaya. - St. Petersburg: Propylaea, 2014. - 164 p. — 200 copies. - Lavrov L.P., Kurbatov Yu.I..

Non-residential buildings Shopping center (glass) • Supermarket • Kindergarten • School • Cinema • Hotel Related concepts Blocked development (Lanehouse) • House-building plant • Townhouse This article is one of the good articles in the Russian section of Wikipedia.

Tolerable and unbearable

Unbearable Series

The buildings belonging to the first series were a temporary solution to the problem of the shortage of housing stock. Their operation should not have lasted more than 25 years.

Note! As practice shows, many of them are still inhabited by guests.

Houses of non-demolishable series have a design life of 50 years. However, studies of such structures conducted a little later showed that their service life can increase to 150 years if major repairs are carried out in the house in a timely manner.

Excerpt characterizing 1-528KP-40 (series of houses)

Suddenly Prince Hippolyte stood up and, stopping everyone with hand signs and asking them to sit down, spoke: “Ah!” aujourd'hui on m'a raconte une anecdote moscovite, charmante: il faut que je vous en regale. Vous m'excusez, vicomte, il faut que je raconte en russe. Autrement on ne sentira pas le sel de l'histoire. [Today I was told a charming Moscow joke; you need to teach them. Excuse me, Viscount, I will tell you in Russian, otherwise the whole point of the anecdote will be lost.] And Prince Hippolyte began to speak Russian with the accent that the French speak when they have been in Russia for a year. Everyone paused: Prince Hippolyte so animatedly and urgently demanded attention to his story. – There is one lady in Moscow, une dame. And she's very stingy. She needed to have two valets de pied [footmen] for the carriage. And very tall. It was to her liking. And she had une femme de chambre [maid], still very tall. She said... Here Prince Hippolyte began to think, apparently having difficulty thinking. “She said... yes, she said: “girl (a la femme de chambre), put on the livree [livery] and come with me, behind the carriage, faire des visites.” [make visits.] Here Prince Hippolyte snorted and laughed much earlier than his listeners, which made an unfavorable impression for the narrator. However, many, including the elderly lady and Anna Pavlovna, smiled. - She went. Suddenly there was a strong wind. The girl lost her hat, and her long hair was combed... Then he could no longer hold on and began to laugh abruptly and through this laughter he said: - And the whole world knew... And that’s how the joke ended. Although it was not clear why he was telling it and why it had to be told in Russian, Anna Pavlovna and others appreciated the social courtesy of Prince Hippolyte, who so pleasantly ended Monsieur Pierre’s unpleasant and ungracious prank. The conversation after the anecdote disintegrated into small, insignificant talk about the future and the past ball, performance, about when and where they would see each other. Having thanked Anna Pavlovna for her charmante soiree [charming evening], the guests began to leave. Pierre was clumsy. Fat, taller than usual, broad, with huge red hands, he, as they say, did not know how to enter a salon and even less knew how to leave it, that is, to say something especially pleasant before leaving. Besides, he was distracted. Getting up, instead of his hat, he grabbed a three-cornered hat with a general's plume and held it, tugging at the plume, until the general asked to return it. But all his absent-mindedness and inability to enter the salon and speak in it were redeemed by an expression of good nature, simplicity and modesty. Anna Pavlovna turned to him and, with Christian meekness expressing forgiveness for his outburst, nodded to him and said: “I hope to see you again, but I also hope that you will change your opinions, my dear Monsieur Pierre,” she said. When she told him this, he did not answer anything, he just leaned over and showed everyone his smile again, which said nothing, except this: “Opinions are opinions, and you see what a kind and nice fellow I am.” Everyone, including Anna Pavlovna, involuntarily felt it. Prince Andrey went out into the hall and, putting his shoulders to the footman who was throwing his cloak on him, listened indifferently to the chatter of his wife with Prince Hippolyte, who also came out into the hall. Prince Hippolyte stood next to the pretty pregnant princess and stubbornly looked straight at her through his lorgnette. “Go, Annette, you’ll catch a cold,” said the little princess, saying goodbye to Anna Pavlovna. “C’est arrete, [It’s decided],” she added quietly. Anna Pavlovna had already managed to talk with Lisa about the matchmaking that she had started between Anatole and the little princess’s sister-in-law. “I hope for you, dear friend,” said Anna Pavlovna, also quietly, “you will write to her and tell me, comment le pere envisagera la chose.” Au revoir, [How the father will look at the matter. Goodbye] - and she left the hall. Prince Hippolyte approached the little princess and, tilting his face close to her, began to tell her something in a half-whisper. Two footmen, one the princess, the other his, waiting for them to finish speaking, stood with a shawl and a riding coat and listened to their incomprehensible French conversation with such faces as if they understood what was being said, but did not want to show it. The princess, as always, spoke smiling and listened laughing. “I’m very glad that I didn’t go to the envoy,” said Prince Ippolit: “boredom... It’s a wonderful evening, isn’t it, wonderful?” “They say that the ball will be very good,” answered the princess, raising her mustache-covered sponge. “All the beautiful women of society will be there.” – Not everything, because you won’t be there; not all,” said Prince Hippolyte, laughing joyfully, and, grabbing the shawl from the footman, even pushed him and began to put it on the princess. Out of awkwardness or deliberately (no one could make out this) he did not lower his arms for a long time when the shawl was already put on, and seemed to be hugging a young woman. She gracefully, but still smiling, pulled away, turned and looked at her husband. Prince Andrei's eyes were closed: he seemed so tired and sleepy. - You are ready? – he asked his wife, looking around her. Prince Hippolyte hastily put on his coat, which, in his new way, was longer than his heels, and, getting tangled in it, ran to the porch after the princess, whom the footman was lifting into the carriage. “Princesse, au revoir, [Princess, goodbye," he shouted, tangling with his tongue as well as with his feet. The princess, picking up her dress, sat down in the darkness of the carriage; her husband was straightening his saber; Prince Ippolit, under the pretext of serving, interfered with everyone. “Excuse me, sir,” Prince Andrei said dryly and unpleasantly in Russian to Prince Ippolit, who was preventing him from passing. “I’m waiting for you, Pierre,” said the same voice of Prince Andrei affectionately and tenderly. The postilion set off, and the carriage rattled its wheels. Prince Hippolyte laughed abruptly, standing on the porch and waiting for the Viscount, whom he promised to take home. “Eh bien, mon cher, votre petite princesse est tres bien, tres bien,” said the Viscount, getting into the carriage with Hippolyte. – Mais très bien. - He kissed the tips of his fingers. - Et tout a fait francaise. [Well, my dear, your little princess is very sweet! Very sweet and perfect Frenchwoman.] Hippolyte snorted and laughed. “Et savez vous que vous etes terrible avec votre petit air innocent,” continued the Viscount. – Je plains le pauvre Mariei, ce petit officier, qui se donne des airs de prince regnant.. [Do you know, you are a terrible person, despite your innocent appearance. I feel sorry for the poor husband, this officer, who poses as a sovereign person.] Hippolyte snorted and said through laughter: “Et vous disiez, que les dames russes ne valaient pas les dames francaises.” Il faut savoir s'y prendre. [And you said that Russian ladies are worse than French ones. You have to be able to take it up.] Pierre, having arrived ahead, like a homely man, went into Prince Andrei’s office and immediately, out of habit, lay down on the sofa, took the first book he came across from the shelf (it was Caesar’s Notes) and began, leaning on his elbow, reading it from middle. -What did you do with m lle Scherer? “She’s going to be completely ill now,” said Prince Andrei, entering the office and rubbing his small, white hands. Pierre turned his whole body so that the sofa creaked, turned his animated face to Prince Andrei, smiled and waved his hand. - No, this abbot is very interesting, but he just doesn’t understand the matter well... In my opinion, eternal peace is possible, but I don’t know how to say it... But not political balance... Prince Andrei was apparently not interested in these abstract conversations. - You can’t, mon cher, [my dear,] say everything you think everywhere. Well, have you finally decided to do something? Will you be a cavalry guard or a diplomat? – asked Prince Andrei after a moment of silence. Pierre sat down on the sofa, tucking his legs under him. – You can imagine, I still don’t know. I don't like either one. - But you have to decide on something? Your father is waiting. From the age of ten, Pierre was sent abroad with his tutor, the abbot, where he stayed until he was twenty. When he returned to Moscow, his father released the abbot and said to the young man: “Now you go to St. Petersburg, look around and choose. I agree to everything. Here is a letter for you to Prince Vasily, and here is money for you. Write about everything, I will help you with everything.” Pierre had been choosing a career for three months and had done nothing. Prince Andrey told him about this choice. Pierre rubbed his forehead. “But he must be a Mason,” he said, meaning the abbot whom he saw at the evening. “All this is nonsense,” Prince Andrei stopped him again, “let’s talk about business.” Were you in the Horse Guards?... - No, you weren’t, but this is what came to my mind, and I wanted to tell you. Now the war is against Napoleon. If this had been a war for freedom, I would have understood; I would have been the first to enter military service; but helping England and Austria against the greatest man in the world... this is not good... Prince Andrei only shrugged his shoulders at Pierre’s childish speeches. He pretended that such nonsense could not be answered; but indeed it was difficult to answer this naive question with anything other than what Prince Andrei answered. “If everyone fought only according to their convictions, there would be no war,” he said. “That would be great,” said Pierre. Prince Andrei grinned. - It may very well be that it would be wonderful, but it will never happen... - Well, why are you going to war? asked Pierre. - For what? I don't know. That's how it should be. Besides, I’m going... - He stopped. “I’m going because this life that I lead here, this life is not for me!” A woman's dress rustled in the next room. As if waking up, Prince Andrei shook himself, and his face took on the same expression that it had in Anna Pavlovna’s living room. Pierre swung his legs off the sofa. The princess entered. She was already in a different, homely, but equally elegant and fresh dress. Prince Andrei stood up, politely moving a chair for her. “Why, I often think,” she spoke, as always, in French, hastily and fussily sitting down in a chair, “why didn’t Annette get married?” How stupid you all are, messurs, for not marrying her. Excuse me, but you don’t understand anything about women. What a debater you are, Monsieur Pierre. “I keep arguing with your husband too; I don’t understand why he wants to go to war,” said Pierre, without any embarrassment (so common in the relationship of a young man to a young woman) addressing the princess. The princess perked up. Apparently, Pierre's words touched her to the quick. - Oh, that’s what I’m saying! - she said. “I don’t understand, I absolutely don’t understand, why men can’t live without war? Why do we women don’t want anything, don’t need anything? Well, you be the judge. I tell him everything: here he is his uncle’s adjutant, the most brilliant position. Everyone knows him so much and appreciates him so much. The other day at the Apraksins’ I heard a lady ask: “C’est ca le fameux prince Andre?” Ma parole d'honneur! [Is this the famous Prince Andrei? Honestly!] – She laughed. - He is so accepted everywhere. He could very easily be an adjutant in the wing. You know, the sovereign spoke to him very graciously. Annette and I talked about how this would be very easy to arrange. How do you think? Pierre looked at Prince Andrei and, noticing that his friend did not like this conversation, did not answer. - When are you leaving? - he asked. - Ah! ne me parlez pas de ce depart, ne m'en parlez pas. Je ne veux pas en entendre parler, [Oh, don’t tell me about this departure! “I don’t want to hear about him,” the princess spoke in the same capriciously playful tone in which she spoke with Hippolyte in the living room, and which obviously did not suit the family circle, where Pierre was, as it were, a member. – Today, when I thought that I needed to break off all these dear relationships... And then, you know, Andre? “She blinked significantly at her husband. – J'ai peur, j'ai peur! [I’m scared, I’m scared!] she whispered, shaking her back. The husband looked at her as if he was surprised to notice that someone else besides him and Pierre was in the room; and with cold politeness he turned inquiringly to his wife: “What are you afraid of, Lisa?” “I can’t understand,” he said. – That’s how all men are selfish; everyone, everyone is selfish! Because of his own whims, God knows why, he abandons me, locks me in the village alone. “With your father and sister, don’t forget,” Prince Andrei said quietly. - Still alone, without my friends... And he wants me not to be afraid. Her tone was already grumbling, her lip lifted, giving her face not a joyful, but a brutal, squirrel-like expression. She fell silent, as if finding it indecent to talk about her pregnancy in front of Pierre, when that was the essence of the matter. “Still, I don’t understand, de quoi vous avez peur, [What are you afraid of," Prince Andrei said slowly, without taking his eyes off his wife. The princess blushed and waved her hands desperately. “Non, Andre, je dis que vous avez tellement, tellement change... [No, Andrei, I say: you have so, so changed...] “Your doctor tells you to go to bed earlier,” said Prince Andrei. - You should go to bed. The princess said nothing, and suddenly her short, whiskered sponge began to tremble; Prince Andrei, standing up and shrugging his shoulders, walked around the room. Pierre looked in surprise and naively through his glasses, first at him, then at the princess, and stirred, as if he, too, wanted to get up, but was again thinking about it. “What does it matter to me that Monsieur Pierre is here,” the little princess suddenly said, and her pretty face suddenly blossomed into a tearful grimace. “I’ve been wanting to tell you for a long time, Andre: why did you change so much towards me?” What I did to you? You're going to the army, you don't feel sorry for me. For what? - Lise! - Prince Andrey just said; but in this word there was a request, a threat, and, most importantly, an assurance that she herself would repent of her words; but she continued hastily: “You treat me like I’m sick or a child.” I see everything. Were you like this six months ago? “Lise, I ask you to stop,” said Prince Andrei even more expressively. Pierre, who became more and more agitated during this conversation, stood up and approached the princess. He seemed unable to bear the sight of tears and was ready to cry himself. - Calm down, princess. It seems so to you, because I assure you, I myself experienced... why... because... No, excuse me, there is no stranger here... No, calm down... Goodbye... Prince Andrei stopped him by the hand. - No, wait, Pierre. The princess is so kind that she will not want to deprive me of the pleasure of spending the evening with you. “No, he only thinks about himself,” said the princess, unable to hold back her angry tears.